Do you have a question?

Get in touch with me. Feel free to call me or send me an e-mail message. I look forward to the dialogue with you!

Conjoint analysis is a method for simulating purchase decision situations, with which the optimal value for each attribute of a product or service can be determined. It offers the possibility to calculate market simulations and to show which product configuration has the greatest market chances or to what extent new products could displace own products already established on the market.

Conjoint analyses can be used for products (e.g. fast moving consumer goods) as well as for services. However, these must be decomposable into characteristics relevant to the purchase decision, which can be varied in their characteristics. The respondents must also be given the product or service alternatives to choose from in a way that is as realistic as possible.

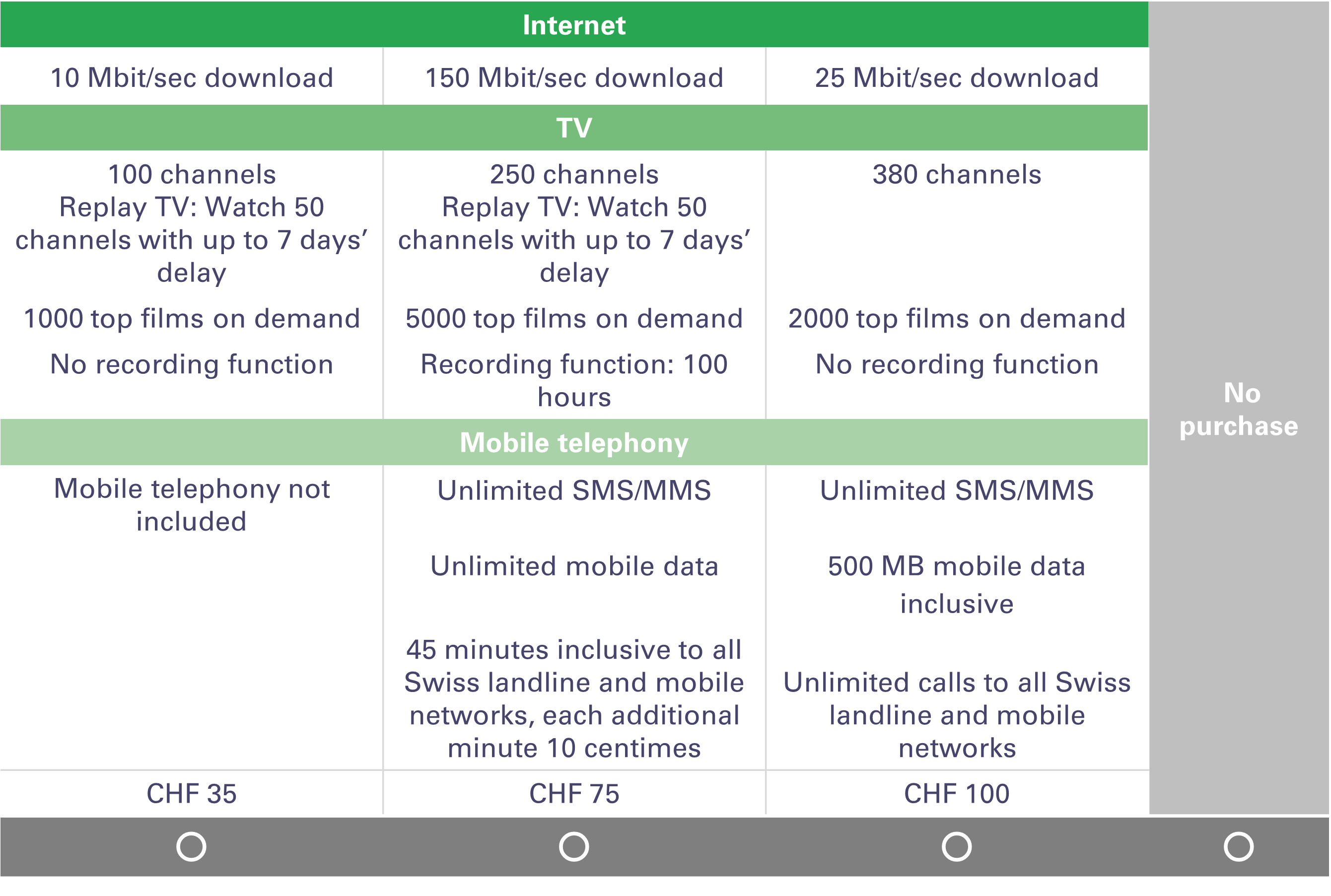

The illustration shows a query example for a choice-based conjoint task: Respondents have to decide for one of the three telecommunication bundles or for “No purchase”. The components of the bundles (light cells in the table) including prices are randomly generated for each task. This choice task is shown up to 20 times with changing content in the Choice Based Conjoint (CBC, see below).

With complex products or services composed of several sub-properties. Furthermore, there should be alternatives to these properties (thus a tablet PC could have various different screen sizes and storage capacities). The conjoint analysis identifies the relative values of each of these properties (partial benefit) and can pinpoint the optimum price for the relevant overall product (sum of all the partial benefits). We apply the following conjoint analyses first and foremost:

In choice-based conjoint, the persons questioned have to choose one of two, three, four or even more products described in detail and presented on one page (discreet choice approach). Since they also have the possibility of deciding against all the products presented (no-choice option) and thus not selecting a product at all, the survey is very similar to a real-life decision-making situation. In CBC, this selection task is presented up to 20 times with varying content.

In CBC, the people questioned are presented with quick and demanding decision-making tasks, even if the products to choose from are only described with a few characteristics. An upper limit of six features should therefore not be exceeded. If more characteristics need to be used, then adaptive conjoint analysis (ACA) is an option. This is broken down into a conventional section, in which the importance of the properties is surveyed, and an actual conjoint section, in which sample sets of properties are put together and presented to those questioned for selection.

Whilst with CBC the product alternatives shown to respondents are not aimed at personal product preferences, the ACBC process offers the opportunity to adapt the products presented to respondents’ preferences. It consists of numerous individual steps, whose content gradually helps to reveal the preference structure of the respondent. The ACBC process is significantly longer than a normal CBC. On the other hand respondents generally find the ACBC process to be more interesting and more involving.

There are two fundamental points of criticism of the conjoint approach, which we counter with different approaches:

All three correction approaches are carried out in close consultation with our clients and depending on the initial situation and the decision-making situation of the respondents. They are used on a case-by-case basis and only if they contribute to an improvement in data quality.

Get in touch with me. Feel free to call me or send me an e-mail message. I look forward to the dialogue with you!